Building a Scrollytelling Visualization

In my last post, I built a visualization of my Spotify data. I used the data to create a scrollyteller, which presents a story as you scroll (if you check out the post, you’ll see what I mean). If you found this interesting and wanted to see how I made it, look no further! Please keep in mind this was my first scrollyteller, but hopefully you’ll find this to be insightful.

There’s two main parts to this project - the graphs and the formatting for the story.

D3 Visualizations

What’s D3? It stands for Data-Driven Documents. A lot of people think of it as a graphing library, but it’s more than that; it’s a manipulation of data at low-level. It might not seem like much at first, but after working with it for a little bit you start to understand what makes it special.

The best D3 tutorial I used was this one from Square. It walks you through the basics of using D3 and all in all was a great introduction.

Why D3 over other libraries? Why not just use Tableau or Excel? Once you look through some projects that used D3, you’ll want to learn it. Seriously, this library is amazing. There are other libraries that fulfill somewhat similar purposes, but D3 is by far the most popular.

Creating a Bar Chart

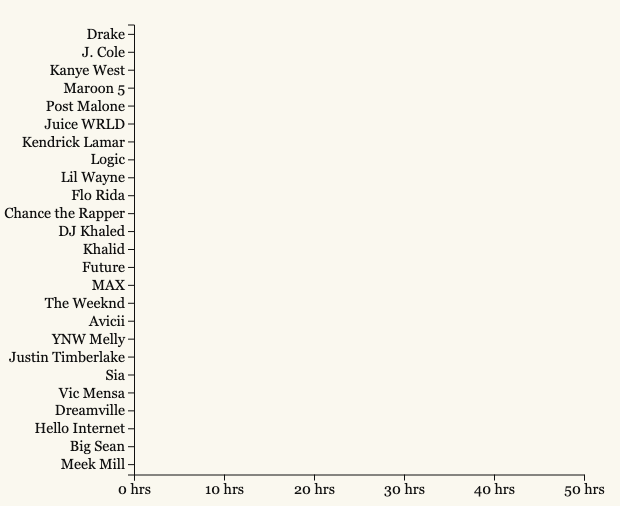

Let’s go through how I built a simple bar chart for the Spotify Visualization post. In that post, I took my Spotify data and mapped it to a barchart for how long I listened to each artist. I’ll walkthrough the code, but I won’t give the data because I think it’s best if you find some other dataset and try to build it yourself (this just means you have to do a little bit more work instead of copy pasting code, but you’ll learn more!).

First, let’s create a bar chart. In something like Excel, this takes a couple of clicks, but in D3, we have to build it from scratch. First, we need to create a “canvas,” if you will, that we can draw the bar chart on. We do this with Scalable Vector Graphics (SVGs).

var svg = d3.select('.chart')

.append('svg')

.attr('width', width)

.attr('height', height)

You’ll notice here we’ve “chained” together several functions; we can do this because when we call each function, it returns an instance of the object itself. So here, we select the HTML element with the class ‘chart,’ add on an SVG element, and then adjust the width and height for our canvas.

Now that we have our canvas, the logical next step is axes. To do this, let’s create some scales to build off. (Note, I say “scales” not “axes” here!)

var scaleArtistY = d3.scaleBand()

.domain(data.map((d)=>d.artist))

.range([margin.top, height-margin.bottom])

var scaleAmountX = d3.scaleLinear()

.domain([0, d3.max(data, (d,i) => d.total_time)])

.range([margin.left, width-margin.right])

.nice();

//nice rounds off values

var scaleAmountColor =

d3.scaleOrdinal(d3.quantize(d3.interpolateWarm, 26))

What’s a scale? Well, think of it as a function from the raw data dimension to the visualization data. Scales are functions that take in raw data, like what year it is for example, and return a concrete dimension for the display, like a pixel location.

We have three dimensions here. The first, scaleArtistY, maps a Spotify artist to a y value. This is what the domain and the range functions are doing, defining the input and outputs. d3.scaleBand() allows us to take categorical variables (like the names of Spotify artists we’re using) to “bands” (read more about it here).

scaleAmountX is the quantifier for how long I’ve listened to each Spotify artist. It uses scaleLinear() because we’re mapping a continuous variable to another continuous range. scaleAmountColor is a way to make the graph look a little bit more aesthetically pleasing.

Next, we define our axes. Remember, this is different from our scales. Axes are the lines you see on your screen, scales are functions that map one value to another.

var yAxis = d3.axisLeft(scaleArtistY)

var xAxis = d3.axisBottom(scaleAmountX)

.tickFormat(val => val + " hrs")

.ticks(4);

Now that we’ve defined our axes, we need to draw them.

//g stands for "group"

svg.append('g')

.style("font-family", font)

.style("font-size", "1vw")

.attr('class', 'y axis')

.attr("transform", `translate(${margin.left},0)`)

.call(yAxis);

svg.append("g")

.style("font-family", font)

.style("font-size", "1vw")

.attr('class', 'x axis')

.attr("transform", `translate(0,${height - margin.bottom})`)

.call(xAxis);

Great! The next step, you might think is to draw the content of the graphs. But before we get there, let’s define some helper variables. There’s an important concept called data binding in D3, but this walkthrough’s goal in brevity will omit this. Data binding is a very important process in D3, so I highly recommend doing some research on this on your own (the Square tutorial above helps out with this).

var barg = svg.append("g");

var rects = barg

.selectAll("rect")

.data(data);

var newRects = rects.enter();

var texts = barg

.selectAll("text")

.data(data)

var newTexts = texts.enter();

Now we’ve got everything setup, it’s time to draw the actual bars!

newRects

.append("rect")

.attr("class", "rect")

.attr("id", (d,i) => i)

.attr("x", margin.left + 2)

.attr("y", (d,i) => scaleArtistY(d.artist))

.attr("width", 0)

.attr("height", (d,i) => scaleArtistY.bandwidth())

.attr("fill", (d,i) => scaleAmountColor(d.total_time))

.attr("opacity", 1)

Hmm, this is just empty. Looking at the previous code, we set the width to 0. Why? Well let’s add in the rest of the code and see.

barg.selectAll("rect")

.transition()

.duration(1000)

.attr("width", (d,i) => scaleAmountX(d.total_time) - margin.left)

Here, we’ve added an transition to the rectangle width. We now have an animation for the bar graph; let’s check it out!

Notice I’ve added text elements to the graph, but it’s nothing too different from what I had done before.

Notice I’ve added text elements to the graph, but it’s nothing too different from what I had done before.

Any plain old graph making software like Excel would not have given us all this flexibility. Yes, there’s some more organization to do beforehand, but it gives us the tools to do whatever we desire. This is because at the core, D3 is not a graphing library but a data manipulation library.

But D3 goes beyond just some fancy animations. There’s so much that can be done with it, and this is only the beginning.

Scrollytelling and more

If you notice on the Spotify Visualization post, the charts animate as you scroll down the page. On the left side, there’s some updating text that describes the visualization as it changes. This beautiful way of demonstrating charts is known as scrollytelling, an aptly chosen portmanteau.

The library I used for this was Scrollama, and there is some example code in the repository. A good guide on making these scrollytellers was this article from the Pudding.

This post does not nearly explain everything that I did when making my Spotify Visualization scrollyteller. If you want to see the full code for this, check it out here. Feel free to reach out if you’ve got any questions!

Hopefully, this post has given you a brief look into what making a scrollyteller entails by showing a simple example alongside with the resources that I’ve used. My personal D3 explorations are just getting started, so stay on the look out for more interesting posts!